Neanderthal Extinction Linked to Peculiarities in their Blood Types

Neanderthal Extinction Linked to Peculiarities in their Blood Types

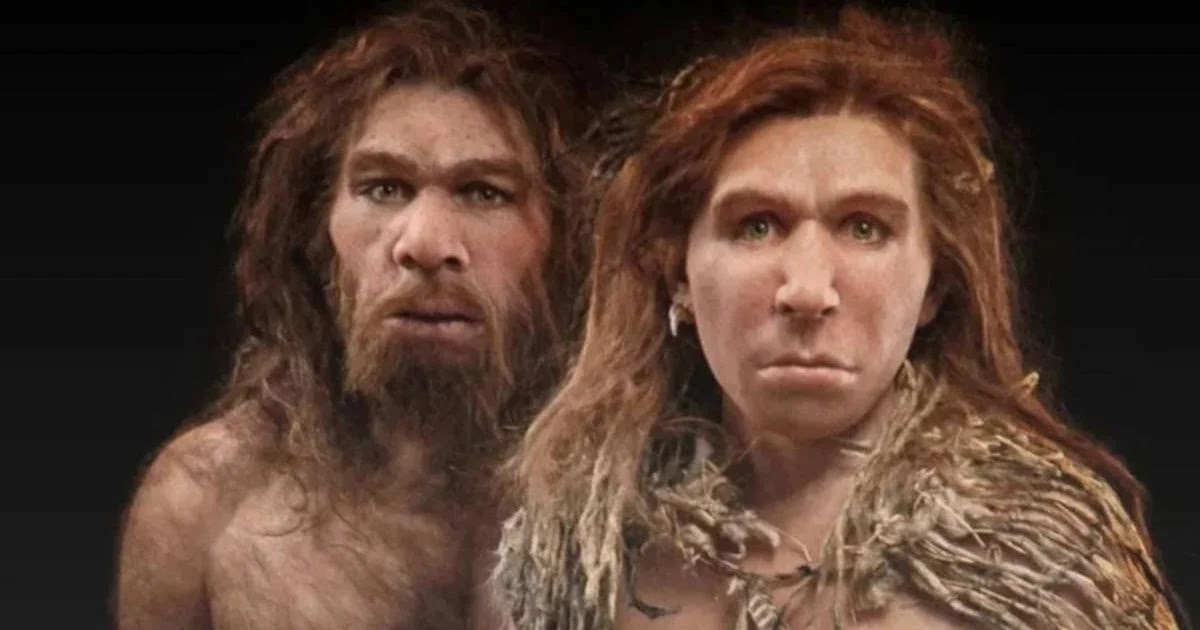

A recent study strongly suggests that when early humans migrated out of Africa, a rapid evolution in their red blood cells may have played a key role in their survival — and potentially contributed to the eventual extinction of Neanderthals, who experienced no such development and suffered because of it.

In a new article published in the journal Scientific Reports, an international team of geneticists explain why these evolutionary changes helped one species but not the other, in the competition for long-term survival. By analyzing the genomes of individuals who lived between 120,000 and 20,000 years ago, recovered from skeletal samples, the researchers discovered that Neanderthals possessed a rare blood group that could have been harmful to their newborns—one that declined in frequency in early humans once they’d begun to move from Africa into Eurasia.

This wasn’t a problem when Neanderthals were mating exclusively with each other. But it meant big trouble for them once they started interbreeding with humans, perhaps serious enough to cause a crash in their population.

How Evolution of Human Blood Doomed the Neanderthals

Blood groups in humans are determined by the presence of specific proteins and sugars, known as antigens, which can be found on the surface of red blood cells. Most people are familiar with the ABO system, which classifies blood into four types: A, B, AB, and O. Each person’s immune system identifies their own blood group as safe, but if a person with type B blood comes into contact with type A blood, say through a transfusion, their antibodies will target the A antigens and reject the new blood as an invader.

- Neanderthal Child Development Was Faster than Humans, Study Reveals

- Study Shows Neanderthals Had Capacity To Produce And Understand Speech

Another key antigen is the Rh factor, which is responsible for the positive or negative designation of blood types. In modern medicine, understanding the combination of these antigens is crucial for procedures like blood transfusions, as compatibility between different types can be an issue.

Side-by-side comparison of the skulls of a modern human and a Neanderthal. (hairymuseummatt/CC BY-SA 2.0).

However, the complexity of red blood cells goes beyond just ABO and Rh — hundreds of additional, lesser-known antigens exist, and they vary from person to person. And their presence or absence can have an impact on a person’s health. These variations have been inherited over millennia, prompting a team of researchers from Aix-Marseille University in France to investigate ancient genomes to explore the evolution of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and early humans with respect to their blood chemistry

"Neanderthals have an Rh blood group that is very rare in modern humans," said Stéphane Mazières, a population geneticist at Aix-Marseille University and the study's lead author, in an email to Live Science. This particular Rh variant, a type of RhD, is incompatible with those found in Denisovans (another human cousin that lived in Asia between 285,000 and 25,000 year ago) and early Homo sapiens.

Mazières added that "for any case of inbreeding between a Neanderthal female and a Homo sapiens or Denisovan male," there was a significant risk of hemolytic disease of the newborn. This condition, which can lead to jaundice, severe anemia, brain damage, or even death, would have been fatal for Neanderthal infants.

Whether this would have been noticed by Neanderthals at some point and seen as a reason not to breed with their cousin-species is unknown. But if it was not recognized, or only recognized after interbreeding had been going on for awhile, it could have very well put Neanderthals on the fast track to extinction, if Neanderthal populations were declining as early humans became more and more prevalent in the regions where they lived.

The Rh-Negative Enigma

The reasons behind the prevalence of the Rh protein in modern humans are still unclear, as is the cause of Rh-negative individuals. However, complications can arise during pregnancy when an Rh-negative person carries an Rh-positive fetus. This is known as Rh incompatibility, which can trigger an immune response that attacks the fetus's red blood cells, leading to hemolytic disease in the newborn.

In modern times, doctors can prevent this issue with an injection of immunoglobulin, a lab-made antibody. But obviously such a treatment did not exist 100,000 years ago.

The study team discovered that the Rh gene variants common in today’s population likely originated from early Homo sapiens, who evolved these traits shortly after migrating out of Africa, possibly while residing on the Persian Plateau. In contrast, Neanderthals had Rh variants that were compatible with each other but remained relatively unchanged for the last 80,000 years of their existence.

- Rh-Negative Blood: An Exotic Bloodline or Random Mutation?

- Humans Used Alternate Migration Route Out of Africa 80,000 Years Ago

Neanderthals' relative isolation (before modern human ancestors arrived from Africa) could explain why their red blood cells evolved so little over time. However, there is still uncertainty about why early humans experienced such rapid diversification in their red blood cell traits — a change that occurred over a period of at least 15,000 years.

"My first thought was that this was due to demographic expansion,” Mazières speculated. He also suggested that "the novel environments of Eurasia may have played a role in maintaining these traits across generations."

Illustration of Neanderthal family gathered around a fire inside a cave. (Free Malaysia Today/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Only DNA Traces of Neanderthals Remain

This research adds another layer to our understanding of human evolution (and Neanderthal evolution, or lack thereof), complementing archaeological and previously discovered genetic evidence. It aligns with the idea that new genetic lineages and technological innovations, including stone tool industries, emerged in the Persian Plateau between 70,000 and 45,000 years ago, helping ensure humans would survive over the long-term.

Meanwhile, the lack of genetic diversity in Neanderthals and Denisovans' red blood cells during the same period suggests they may have experienced inbreeding and population decline, which ultimately contributed to their extinction. While these two species did ultimately disappear, their DNA is actually still around, comprising a small percentage of the currently existing human genome (a direct result of historical interbreeding).